|

|

The subject of today’s discussion is “emanation”. In Bengali it means utsárańa. If something is produced from something and gradually moves forward towards greater manifestation it is called utsárańa. At the root of emanation is cause or causal factor, which is in a dormant condition at the outset. We know that the sprout comes from the seed. The potential for vastness or extensiveness lies in a dormant condition within the seed. Under favourable conditions the sprout first comes forth and thereafter it flows on the path of emanation, gradually moving forward on the path of diffusion. All of this gets its expression from the seed, from the seed-form, from the fundamental or rudimental condition. Of course, there is a fundamental difference between the two words “rudimental” and “fundamental”. “Fundamental” means “pertaining to the foundation” and “rudimental” means “radical” or “pertaining to the seed”. They are both Latin words. One comes directly from Latin and the other comes indirectly through the medium of old German, as has the word “noumenal”.

This sprouting – that is, this movement from the unmanifest to the manifest state – is vyaktiikarańa [manifestation] or utsárańa. Incidentally I should point out here that the word vyaktiikarańa is spelt with ii because if the latter word in a compound word ends with anat́ or kta and the first word ends with a then ii is inserted at the end of the first word. For example, bhasma + bhúta = bhasmiibhúta; ghana + bhúta = ghaniibhúta; nava + karańa = naviikarańa, and so on.

This manifestation or emanation is vibrational, and this vibration moves in a contractive-expansive flow, a systaltic order which moves in crests and troughs. For example, the flow of river-water is not straight and continuous; it moves in waves of crest and trough. The wave impulse that is present in the first phase of emanation wanes in the subsequent phase due to the different blows and counterblows. It is similar to a river which flows swiftly in the mountains but which slows down considerably when it passes through the plains and reaches the delta before finally merging in the sea.

This rule is equally applicable to language. Language also changes in the process of maintaining adjustment with the changes in time, place and person, and this change is irresistible. It cannot be held in check. For example, Glowing Chester → Glow-Chester → Glouchester → Gloucester. The insect that we call jonáki poká in Bengali is called “glow-worm” or “fire-worm” in English. In Sanskrit it is called khadyot, while in Urdu it is called jugnu, and bhagjogni in the languages of Bihar. Normally these insects live in low-lying wet areas. In one low-lying area in England there were a great number of glow-worms so the people began calling the place Glowing-Chester; through distortion the modern name became Glaśt́ár although it is still spelled “Gloucester”.

Similarly, from the word “house-wife” comes háuzif and from that comes házif (pronounced like “huzif” in English). This házif means “where odds and ends are kept”. However when it means “mistress of the house” then it is pronounced háuz-wáif although the spelling is the same. The modern pronunciation of ed́inbará comes from ed́inbárg (Edinburgh) although the English spelling remains as it was. Distortion has taken place in the Scottish pronunciation. The English for “the price of this thing is six pennies” is “it is six pennies worth” – “six pennies worth” → “six pen-worth”. There are many such examples in Bengali. For example, the word keleuṋkárii [scandal] in Bengali comes from kalauṋkakárii, gámchá [towel] from gá-mochá, yácchetái [whatever one pleases] from yá-icche-tái, eblá [this part of the day] from e-belá, oblá from o-belá [that part of the day], rovvár [Sunday] from ravivár, tálbelim [student] from tálib-e-ilm.

Another well-known word of this kind in Bengali is eyo [woman whose husband is alive]. Its origin is the Sanskrit word avidhavá. Avidhavá in Sanskrit → avihavá in Prákrta → aihaá in Demi-Prákrta → áiha in old Bengali → eyo in modern Bengali. Vidhavá [widow] women are not eyo. The word dhava has three meanings. The first is “cloth”, the second is “white” and the third is “husband”. One who has a husband is sadhavá and one whose husband is dead is vidhavá. An unmarried daughter is adhavá.

Anyhow there is no scope for cessation in the change that language undergoes on the path of emanation. So from dadhi comes dahi → dai [curd] (dae is incorrect); vadhú → vahu → vau [wife] (vao is incorrect); madhu → mahu → mau [honey] (mao is incorrect); sádhu [honest] → sáhu → sáu [merchant]. In ancient India there was a custom for merchants to use the title “Sádhu” [honest] at the end of their name. This was done to keep them on the honest path and to keep the tendency to stay on the honest path awake in their minds, despite the fact that they were involved in business activities. The modern word sáu comes from the word sádhu.

From the Sanskrit word gátramokśańa comes gátramocchana → gá-mochá → gámchá [towel].

A well-known Bengali word is álgoch. The origin of this word is the Sanskrit word alagnasparsha. Alagnasparsha → alaggapaccha → alggaccha → álgáchonyá → álgoch, that is, “non-continuous touching”.

We often say yácchetái-yácchetái, vitikicchiri-vitikicchiri. Actually there is no such word as yácchetái. The word is yá-icche-tái, that is, “that which is not bound by rules” or “according to one’s fancy or liking”. The word vitikicchiri [ugly] has two equally applicable sources. One is vigatashrii → vigatachiri → vitikicchiri. The other is vigatakutsa → vigatakicchi → vitikicchiri. Shrii [charm] is called chiri in spoken Bengali. Áhá! Kathár kii chiri dekha ná! [Alas! Just see how charming his words are!]. There is a material called chiri used alongside the welcoming basket in the Calcutta area during the wedding rites performed by the married women. In village Bengali the nickname of someone whose good name is Shriipati is usually chiru. The Arabic tálib-ul-ilm and Farsi tálib-e-ilm becomes tálbelim in spoken Urdu. However these are not exactly examples of emanation but rather specialties of distortion.

This process of emanation is not limited to human language. Its influence can be noticed in the human physical constitution as well. The composition of the human body changes with the change in eras. In olden times people’s hands were comparatively longer than they are today. Arms reaching down towards the knees used to be considered a sign of handsomeness in men. Kashiram Das in his description of Arjuna has written:

Dekha dvija manasija jiniyá múrati

Padmapatra yugnanetra parashaye shruti

Dekha cáru yugmabhuru lalát́a prasára

Kii sánanda gati manda matta kariivara

Bhujayuga ninde náge ájánulambita

Agni-áḿshu yena páḿshujále ácchádita

[Look at the young brahman, more handsome than Cupid, with eyebrows that extend to his eyes. Look at his excellent broad forehead and his joyful majestic gait like a kingly elephant. His arms down to his knees put even the snakes to shame. His fiery countenance seems to be enveloped in ashes.]

It may sound funny nowadays but it is quite true that there was a time when people could wag their ears to drive away flies and mosquitoes just as cows, horses and other animals can do today. Nowadays if a fly lands on our ear we can shoo it away with our hand. Since the use of the hand has increased in modern times people have lost the capacity to move their ears. Similarly, at one time human beings had a tail like other animals. One thing should be pointed out here. Many people say lej or lyáj instead of nyáj [tail] but this is incorrect. Due to specific linguistic rules nyáj can come from the Sanskrit nyuvjaka but lej or lyáj cannot. Nor does the word come from láungula because láungula does not have a ja. The Bengali word derived from the Sanskrit láungula is neuṋgun. I have heard this word used in Birbhum. I have heard this folk verse:

Chutore kát́h kát́e bagáte neuṋgun náŕe

[a carpenter cuts wood/a heron moves its tail]

In that era people used to live in trees. They used to secure themselves to the tree or the tree branch with their tail so that they would not fall out of the tree while they were asleep. Later on, when human beings began to build temporary dwellings in the trees, the possibility of falling out diminished. Naturally, since the need for a tail diminished, the tail became smaller. Later still, when human beings learned to build permanent dwellings on the ground the need for a tail completely disappeared. Since there is no need for a tail now, there is no tail. The need for a tail disappeared some hundreds of thousands of years ago. There is, however, a truncated bone at the base of the backbone which is a carryover from that past time. It is present in the foetus while it is in its mother’s womb. Thereafter the tail does not grow in proportion to the rest of the body. By the time the human child is born the tail is no longer outside the body. A somewhat similar thing happens with frogs. The tadpole has a tail but when it gets bigger it falls off. This all happens in the path of emanation.

In those days there was little security in people’s lives. On one side there were fierce animals and on the other a scarcity of food. Both of these were constants. Nowadays if there is a scarcity of food in one place people can bring food materials from someplace else but that was not possible then. If food appeared one day there was no certainty [nishcitatá] that it would appear the next.(1) Due to these kinds of circumstances human beings used to have an appendix to their intestines for accumulated or excess food. As it was needed this food would stimulate salivation in the mouth and be fully eaten and digested. The proper eating and digesting of the surplus food in the appendix is called romanthana in Sanskrit and jábar kát́á in Bengali. In good English we call it “rumination” and in spoken English “chewing the cud”. Many herbivorous (vegetarian) animals still ruminate and a need still exists for it in their wild state. As the certainty of food supplies gradually increased, the need for a corporal appendix to the intestines lessened. Eventually there was even not the slightest need for it. Today a small vestige of it remains in the human body although it is no longer used in times of distress. Human beings have lost the capacity to ruminate.

As with language, human dress and clothing also shows the clear influence of emanation. People’s dress changes according to the geography and the weather. For example, the kind of clothes that people wear in hot countries is practically useless in cold countries. In rainy countries it becomes troublesome to walk around in coat and pants when the roads get muddy. So the people in such countries wear dhotis and similar kinds of clothes that can easily be hiked up above the knee and out of the mud’s reach when there is the need. It is perhaps for this reason that the traditional Bengali dress was a dhoti and a shawl or loose upper garment. Nowadays, with the improvements in the roads, people are wearing pants. However if they need to go down to the fields they change from pants to dhoti or lungi.

In those days people did not wear stitched clothes. At first they did not wear them because they did not know about sewing. Later on, sewn clothes were not worn partly due to a superstition based on them not having been worn before, and partly due to practical difficulties. Still today the bridegroom does not wear sewn clothes during the wedding in orthodox Hindu society. For a certain time during the wedding they have to wear dhoti and shawl or dhoti and garad [a type of silk fabric].

The lungi [sarong] is a common Bengali dress. Actually it is not Bengali, per se. Luuṋgi is a Burmese word and the dress is also Burmese. At one time many people from Chittagong went to Burma to find work. They learned to wear it there and then introduced it to this country. During my childhood I noticed that many conservative families did not like to wear lungis. Nowadays people’s point of view has changed and wearing it has become quite natural.

As with the change in dress, a great change has come about in social customs and practices. According to the prevalent Bengali social practice, people were sent to bring or collect news between houses related by marriage. Along with this there was the custom of sending dhotis, saris and sweets. It was considered somewhat unbecoming if someone arrived empty-handed to receive or bring news, thus the practice of sending clothes and sweets was introduced. “News” used to be called tattva in refined Bengali in those days. Gradually this dhoti, sari and sweets came within the purview of the word tattva. In other words, “tattva has arrived from the boy’s father-in-law’s house” referred to what kind of clothes and what kind of sweets had arrived – the word had become bigger. Later on, when the word tattva had lost its actual or genuine meaning, a number of Calcutta confectioners (most likely residents of Hooghly District’s Janái village) came up with a special variety of sweet made from cháná,(2) which was different from the mańd́á, káncá gollá or mákhá sandesh that were prevalent in Bengal prior to that. Since it became a favourite practice to send along some of this cháná sweet with the tattva, the name of the new sweet became sandesh which actually means “all sorts of news”.

Subsequently different varieties of sandesh came into existence under the dextrous magic hands of the confectioners. Confectioners of Púrvasthalii in Burdwan District invented tálsháns sandesh. During our childhood days the sandesh of Naŕiyá (Faridpur District) and Nát́or (this place in Rajshahi District had, at one time, made a name for itself in confectionery, clay handicrafts and music) were also famous. It is not so that the confectioners of Pábná District’s Sirájganj proved their artistry by making camcam. First they made sandesh from nalen guŕ. The confectioners of Midnapore’s Rádhámańi made átá sandesh and in Murshidabad dedo sandesh. The káncá gollá of Muŕágáchá and Sátkśiirá reappeared in a new form with a new allure. In Calcutta one cannot go without mentioning ávár-kháva sandesh. Rather than making the list any longer I will end here with the name kaŕá pák sandesh. If I go on any more the reader’s tongue may become an obstacle to their reading of the book.

I will take a brief respite here to point out that there is no mention of cháná in old Bengali literature. In the history of the Middle Ages kśiir sweets and khoyá sweets [condensed milk sweets] (cánchá kśiir or cánchi in the spoken language of Murshidabad) are mentioned. Mańd́á is also mentioned in the Middle Ages, but it is not known exactly how mańd́á was prepared. The kind of sandesh which is spoken about in the Hari lut́ song is not in any ancient book.

Lágla harir lut́er báhár lut́e ne re torá

Cini-sandesh phul-bátáshá mańd́á joŕá joŕá

chele pile kuŕiye khele kende mare buŕá

Tári májhe hát báŕála vrajer mákhanacorá

[Now begins the distribution of Hari lut́ (the Lord’s favours). Try to procure as much as you can – cini-sandesh, phul bátása, mańd́á (varieties of sweets) – the young children collected lots of sweets but the old people missed out and were crying. And in the crowd our beloved Krśńa stretched out his palms.]

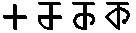

Emanation also affects script and letters. I have already mentioned that a language survives approximately one thousand years. Individual scripts, however, last about two thousand years. Written script did not exist at the beginning of the Yajurvedic era. Written script was invented in India towards the end of that era, that is, about five thousand years ago. At the time when script was invented the sages thought that the creation was a composite of a-u-ma, that is, creation, preservation and destruction. However, the manifest universe is a result of the influence of the guńas of prakrti over consciousness – the supremacy of the binding faculty over the cognitive faculty. In other words, Parama Puruśa comes within the jurisdiction of the binding power of prakrti. This manifest universe is called saḿvrttibodhicitta in the Buddhist nomenclature and káryabrahma (expressed universe) in Aryan nomenclature. In order to indicate this state of puruśa and prakrti a vertical line is used for puruśa and a horizontal line is used for prakrti. Together the two form a cross (+) which signifies káryabrahma or the created universe. The biija [seed] mantra of káryabrahma is ka so this cross became ka in the Bráhmii script. Through the process of writing the Bráhmii ka quickly it became transformed through distortion into today’s letter ka. For example:

Hence we see that in the case of written script emanation also remains intact. The name of the first script invented by the people of India is Bráhmii or Kharośt́ii script. With the passage of time this Bráhmii-Kharośt́ii script evolved into three separate scripts. The name of the distorted script to the southwest of Allahabad is Náradá script. The distorted form to the northwest of Allahabad is Sáradá script. The script that arose in Allahabad and the lands east of there is known as Kut́ilá script.

The area where Náradá script was used included the western areas of modern Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Sindhu, Gujarat and Maharashtra. The Nágar pandits of Gujarat wrote many Sanskrit compositions in Náradá script. Later the script was named Nágarii after them. When they wrote their local language in this script they used to call it Deshii Nágarii or Moŕi. When they wrote Sanskrit (devabháśá) they would write with conjuncts by joining the upper lines [mátrá]. Then they would call the script Devanágarii. Although the modern Gujarati script is Deshiinágarii and does not have mátrá, it does have conjuncts. Among the Moŕi scripts that were used to write the different languages of Rajasthan (Marwari, Mevárii, Haŕaoti, D́hund́háru, Meváti, etc.), western Madhya Pradesh (Málavii, Bundelii), and Maharashtra (Marathi, Varáŕi, Khándeshii, Koḿkanii), Maharashtra’s Moŕi has conjuncts in certain circumstances. However the remaining Moŕi scripts did not and do not have conjuncts. Although modern Marathi books and so forth are printed in Devanágarii script, Devanágarii is not Maharashtra’s script. The Moŕi scripts of Rajasthan (Curuwalii, Yodhpurii, Jhunjhunwalii, etc.) are still commonly used by the general public, especially by merchants. Sindhu’s script is not used for printing modern-day books and so on. Books in Sindhi are now printed with Farsi script, however the old Sindhi script, or Láháńd́ei, is still prevalent among merchants.

The northwestern Sáradá script evolved into several branches. The T́ekŕi, T́egŕi or T́eḿŕei (this script is a close relative of Tibetan script) scripts of the Himalayan mountain regions, Laddaki script (it is also a close relative of Tibetan script), Kashmiri Sáradá (the script in which the modern-day Kashmir pandits write Sanskrit), and Duggardeshii Sáradá (the script of Jammu’s Dogri language), etc. are all distortions of the ancient Sáradá script. The script in which modern-day Panjabi is written is known as Guŕmukhii script. It is not a natural distortion of Sáradá. The Sikh guru, Arjanadeva, introduced this script (there is some difference of opinion regarding this). This script does not have full conjuncts either, however if some effort is made conjuncts can be introduced. This will eliminate the need to write words such as skul, st́ap, st́eshan, etc. as sakul, satap, sat́eshan.

The pandits did not write down the Vedas for a long time, even after the invention of script. They used to believe that the Vedas should not be written down since their forefathers had not done so. Had they looked into it a little more deeply they would have realized that the Vedas were not written down in ancient times because written script did not exist. Later, when the Vedas could no longer be committed to memory, the Kashmir pandits were the first to write them down and they did so in this distorted Sáradá script.(3)

Távat Kashmiiradeshasyád paiṋcáshatyojanátmakah Similarly, we have ajeyameru, that is, “invincible land”. From this comes Ajamiir, not Ájamiir or Ájamiiŕ. Both of these are incorrect.

Although the scientific name of the script that arose in the lands east of Allahabad is Kut́ilá, it is better known as Shriiharśa in the annals of history. The gold coins of the emperor Harśavarddhan were inscribed with this script. It has been found in Kaoshámbi near Allahabad. Modern Bengali, Maethilii, Manipuri, Assamese and Oriya are written in this script. The scripts of Angika, Bhojpuri, Magahii, Chattisgarhi and Nagpuri are also Shriiharśa scripts, but since the people have forgotten their mother scripts and have not been able to create a developed literature of their own up until now, they do their writing and reading nowadays in Hindi. Since Hindi books are printed in Devanágarii script they are more familiar with Devanágarii script.

Oriya script is also Shriiharśa script but the people of those days used to write on palm leaves with a type of iron spud. In order to keep the palm leaves from being torn by the iron spud they rounded off the corners. Thus the modern-day Oriya script looks somewhat circular. Actually Bengali script and Oriya script are the same. The letters of Bengali script have corners, that is, they are angular, while Oriya script is circular. So in the olden days Bengali script used to be called the Gaoŕiiya [Bengali] style of Kut́ilá script and Oriya used to be called the Od́ra style of Kut́ilá script.

The effect of emanation can also be seen in Bengali script. For example, in old Bengali ya used to be joined to the original letter in order to indicate a conjunct with ya. Formerly, all ya-conjuncts were written the way dya is written today (দ্য). In other words a kind of curved ya was written after the letter. This is no longer done in modern Bengali. Previously, kya, dya, tya, bhya, etc. used to be written:

In old Bengali one ta was written underneath the other to indicate tta. Nowadays, however, the tail of the upper ta does not extend back up and the hem of the lower ta begins where the tail leaves off; the letter looks like the letter o. The difference is that tta has an upper line [mátrá] while the o does not. Similarly, the conjunct tra was written with a ra below the ta. Nowadays the tail of ta does not extend back up and the hem of the ra begins where it leaves off. The letter looks like the letter e, the difference being that the letter e does not have a mátrá while the conjunct tra does. If you look at any of the Bengali compound letters you will find that they are actually a proper blending of the original letters. This blending results from taking the path of emanation.

We were talking about the Sáradá, Náradá and Kut́ilá scripts. The Sáradá script developed from the Bráhmii script; it achieved its full form about thirteen hundred years ago. Similarly, the Kut́ilá script achieved its maturity about eleven hundred years ago and the Nágarii script about eight hundred years ago. Thus very old Sanskrit manuscripts can be found in this Sáradá script. Moderately old manuscripts are found in Kut́ilá or Shriiharśa script. Nowadays those who are involved in deciphering obscure passages of old Sanskrit texts and reprinting those texts cannot avoid taking the help of scholars versed in the Sáradá and Shriiharśa scripts. During British rule, when arrangements were made for the study of Sanskrit in universities, there was a need felt to print the textbooks in a specific script so they began printing them in Devanágarii script. The use of Devanágarii script instead of Shriiharśa for Sanskrit in Varanasi, the then centre of Sanskrit study, became common at that time despite the fact that the local script was Shriiharśa and that Shriiharśa is found on stone engravings recovered there. However the pandits at Sanskrit schools in different parts of India used to write Sanskrit in their customary local script and still do so today. So no one should harbour the conception that Devanágarii is Sanskrit’s only script. Actually Sanskrit does not have its own script. Every script commonly used in different parts of India is Sanskrit’s script. Among these, the Sáradá, Shriiharśa and the south Indian scripts are older than Devanágarii.

As with Bengali script, the effect of emanation can be seen in pronunciation as well. In old Bengali ya, ma and va used to retain their separate pronunciation when they occurred as conjuncts; however in modern Bengali, that is, for the last one thousand years, they no longer have their own separate pronunciation. For example, in modern Bengali we write padmá [lotus] but we read it paddá because in modern Bengali the rule is that whenever va, ma or ya are conjuncted to a consonant the pronunciation of that consonant is doubled – va, ma or ya are not pronounced. However a thousand years ago in old Bengali padmá was called padumá, that is, the pronunciation of padmá was certainly pad-má.

Ek so padumá caośat́t́i pákhuŕi

Tenmadhye nácantii d́omnii vápuŕii

[In the sixty-four Tantras it is mentioned that there is a one hundred-petaled lotus in which is dancing the Naeratma Devii, the adorable entity of the mystics.]

The word vápuŕi means “loving daughter”. In old Bengali the suffix uŕii was added in feminine gender to indicate love and affection. For example, bahuŕii, jhiurii, There is this description of a flood in a folk-verse of Faridpur District:

Kata bau jhiuŕii sári sári bháisyá cali yáy

[How many loving daughters and daugher-in-laws are floating away.]

And in old Bengali:

Káhár váhuŕii tumi káhár jhiuŕii

Satya kari bale yáo

Bujhite ná pári

[Whose váhuŕii are you, whose jhiuŕii/tell me the truth/I can’t understand]

Shváshuŕii [mother-in-law] is called shvásh in north India (it is pronounced sás there). By adding the suffix uŕii it becomes shváshuŕii in Bengali. Sháuŕii is also used in Rarhi Bengali.

We write lakśmii but nowadays we pronounce it lakkhii. However in old Bengali its pronunciation was lachmii.

Lachmii cáhite dáridrya beŕala máńik háránu hele

[I prayed for more wealth but unfortunately I became much poorer. I lost the precious jewel due to sheer negligence.]

One writes svámii but nowadays it is pronounced sámii. However in old Bengali it was pronounced soámii. The people of the Burdwan area, especially the women, still pronounce dvádashii doádashii [twelfth]. They pronounce jyánta jiianta [living].

This kind of change is inevitable in language, script, pronunciation, and so on. Although it may be a bit off the subject, change comes about not only in the beauty of things shaped by human beings but also, it can be mentioned, in the case of cuisine. Spices [mashalá] were not used as much in Bengali cuisine as they are today. The word itself, mashalá, is not native to this country. The word is Farsi (mashallá). As with Bengal, the use of spices in England at that time was also extremely limited. In fact, even the word “spice” is not originally English. Nowadays spices are used extensively in Bengal but the use of spices in the kitchens of England has not increased at the same rate. In old Bengal cumin, black pepper, long pepper, coriander and turmeric were used as spices. At that time chilli had yet to arrive in this country.(4) The use of páncphoŕan [five seasonings] began approximately six hundred and fifty years ago (Sanskrit paiṋcasphot́ana, Oriya paiṋcaphut́áni). After putting the spices in the cooking pot it not only gives off a scent for a long time but sound as well. So if someone is speaking with the intention of keeping the original discussion alive, we say o phoŕan kát́che [she is stir-frying spices]. The practice of singeing d́ál [sántláno] in oil is also around six hundred and fifty years old. The word sántláno in Calcutta Bengali comes from the Sanskrit word santtulana. Although the word sántláno is also used in the villages of Burdwan, the word sambará is more popular in the local language.

There is no doubt that both vegetarian and non-vegetarian soups were common at that time. However, since spices were not used as much, hot spices [jhál] were used more in the soups. For this reason the vegetarian soup became known as jháler jhol. A special kind of pulse ball was also made for the soup. Depending on which kind it was, it was known as jholer baŕi or jháler baŕi. Often different kinds of ornaments were also made in the form of these balls. The women in the rural areas of Midnapore can still make these ornamental vaŕi very beautifully.

Hence we see that change occurs in every aspect or expression of human life while maintaining adjustment with this constantly moving universe. This stream of change has been flowing since the very first glimpse of the dawn of human civilization and culture; it has passed through the ancient and medieval eras and finally reached the threshold of the modern era, and this stream will remain unchecked in the future as well. In all aspects of human life – literature, art, language, script, everywhere – the effect of this principle of emanation is unmistakable. It has never been held in check, nor will it ever be. The flooding of this Damodar river cannot be held back by sandbags.

Footnotes

(1) Nih – ci (verbal root) + al = nishcaya. The word itself is a noun. Ghain alao puḿsi, that is, the word is a masculine noun. So where is the scope for adding tá [“ness”] and making it twice into an abstract noun? Thus the word nishcayatá is completely wrong. Instead it should be written either nishcaya or nishcitatá. If one wants to make it into an abstract noun as one does in English by adding “ness” then it has to be written nishcitatá. Otherwise nishcaya will also work.

(2) A curd prepared by heating milk, then adding a curdling agent such as lime juice. –Trans.

(3) The name of this land is Kashmiira, not Káshmiira. The name of the meru or land where the Kash community used to live was “Kash-meru”. The Sanskrit word kashmiira was created from this “Kash-meru”. So káshmiira means “of the land of Kashmiira” and káshmiirii means “woman of the land of Kashmiira”. Thus if anyone is called a káshmiirii pandit it implies that the person is a woman. In Kahlan’s Rájataraunginii one comes across these lines: Sáradámat́hamárabhya kumkumádritatáḿtakah

(4) Research will have to be done to find out what the people of Rarh ate with their puffed rice in place of chilli. There were no potatoes either so there was no álu-caccaŕi. But of course they did have ekho guŕ.